Heritage

The text and images below are taken from A History: The Assembly House Norwich a booklet written by Nick Stone in 2017 on behalf of The Assembly House Trust. Copies are available for free from The House, or click here to download a PDF version.

Click one of the headings from the timeline below to jump to a section, or scroll down the page to read each in turn.

-

Beginnings

The chapel and college of St Mary in the Fields.

-

Change

After the dissolution: the creation of Chapply Field House.

-

Moving on

Thomas Ivory and the early Assembly House.

-

The Victorians

The decline of the assembly and the new entertainment.

-

The Noverres

Ballet, swords, and the spirit of dance.

-

Decline

A school, a warehouse and a war.

-

Regeneration

Building the future – modern development and the trust.

-

The Fire and its aftermath

The new improved Assembly House.

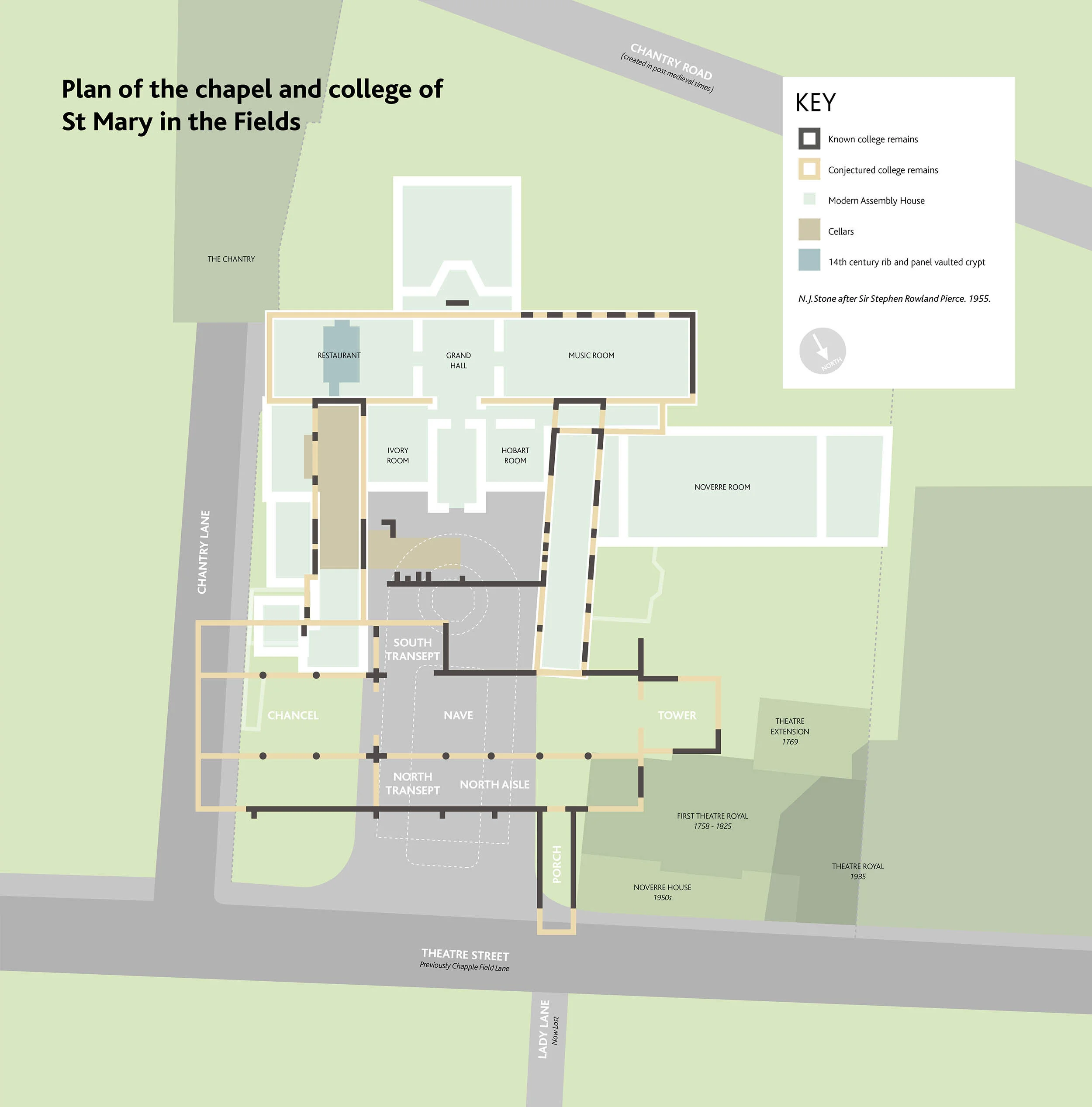

A projection of what the chapel may have looked like in the 14th century, based on evidence from an archaeological dig in 1901 and information acquired during the works of 1947 to 1950.

Stephen Rowland Pierce, January 1950.

Beginnings

The chapel and college of St Mary in the Fields

1248-1658

The Assembly House site sits in an area of Norwich which until the 13th century would have still been largely crofts and fields, just on the edge of the Norman settlement in what became the French quarter. The city wall, which runs along the edge of Chapel Field and around the city, was yet to be built. Beneath the site and in the fabric of the house, parts of the early buildings still lie mostly hidden. They form the remains of the medieval chapel and college of St Mary in the Fields (St Mary de Campo).

In 1248 the land was granted to John Le Brun. He founded the hospital of the Blessed Virgin Mary here with the assistance of his brothers, who gave the advowson or legal right to their churches: St Mary Unbrent, St George Tombland and St Andrew.

In 1278 Le Brun became the Dean of what had by then had become a secular college, and was in charge of the community within; a Chancellor and a Treasurer, a Precentor to lead the singing, Prebendaries who effectively administered it and drew a stipend from its endowments, plus lay-clerks who formed the choir.

The Chapel of St Mary in the Field was an important entity. It grew during a period of tension between the people of the growing city and the power of the cathedral. The dedication to Mary and the foundation of the Guild of Corpus Christi may relate to Le Burn’s conjectured involvement in the riots in Tombland against the cathedral and his attempt to curry favour with Rome. As an entity the chapel and college provided a bridge between the cathedral, the people and the city. As a result it received civic funds, bequests and support from the city.

In 1388 the college acquired the advowson to St Peter Mancroft, then in a particularly poor state. The college also held several other churches in Norfolk, bringing the total, including the chapel in the fields, to nine.

The college chancel was rebuilt between 1425 and 1435, with other areas restored from 1444; and a rood loft built in 1501. Before the Guildhall was built the college had come to be used as a meeting place for the city corporation, the tradition of civic assemblies running deep in the site.

The college ceased at the dissolution of the monasteries in 1544 under the last Dean, Miles Spencer, and was surrendered to Henry VIII. Two years later the site was granted back to Spencer, now the Archdeacon of Norwich. He fulfilled his legal obligation and the chapel was demolished. The remaining buildings were also slowly pulled down and sold while part of the college was turned into his residence.

The area around the lost college and chapel is echoed in the street names: Chapel Field Gardens was part of the precinct and close which originally stretched back to the city wall, and Chapply Fields (now Chapel Field) stretched almost as far as St Giles’ Gate.

Other street names still bear the area’s history. Chantry Lane and Chantry Road both remember an aspect of its religious life too. Lady or Lady’s Lane, now under the Forum, may have been titled as such as a processional way to the Church, opening as it did directly opposite the original porch.

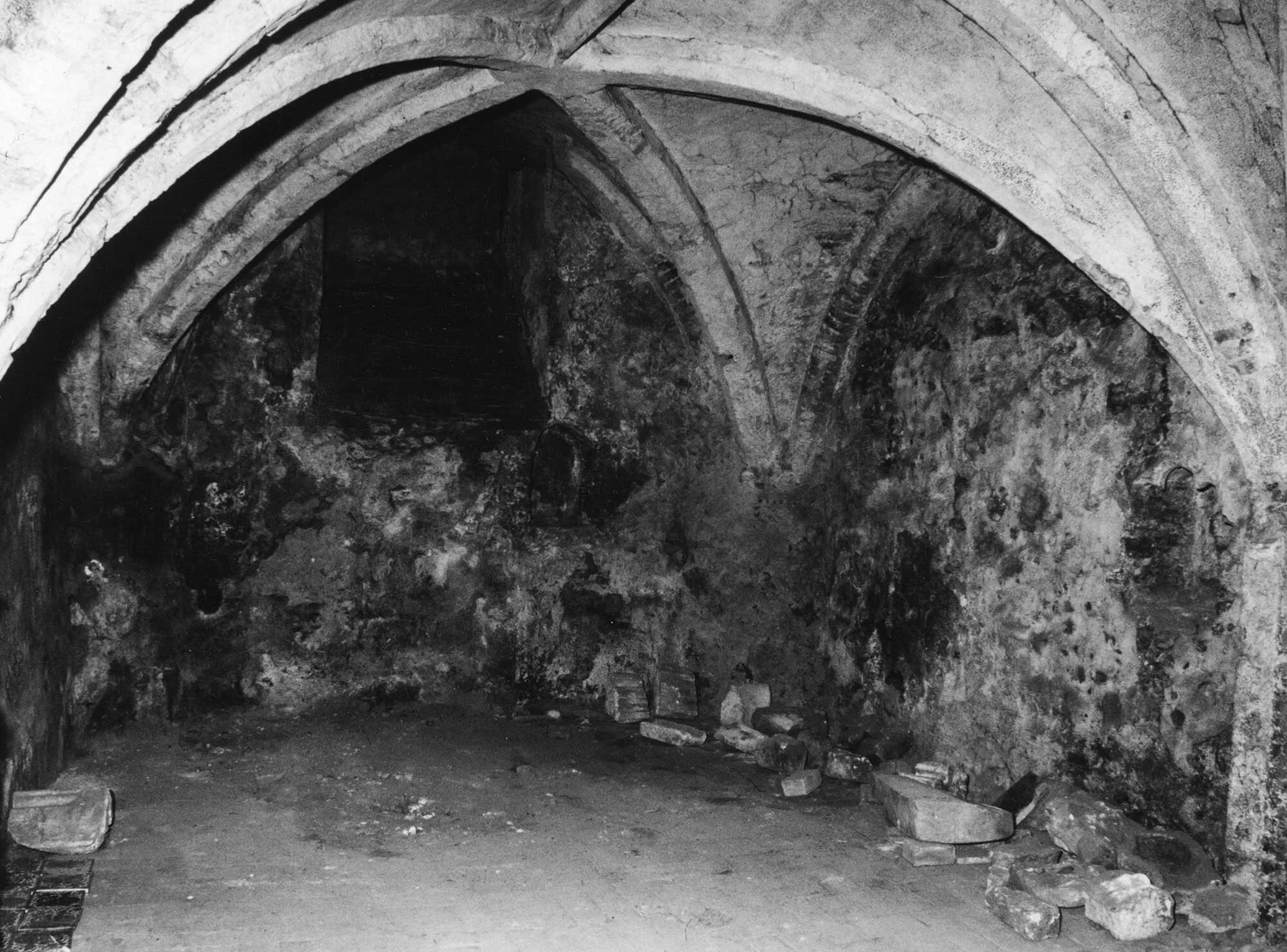

The vaulting on the Medieval crypt under the Music Room. The oldest part of a complex of cellars under the building.

IW collection.

Elements of the building live on; some of the fabric still exists in the current Assembly House: the footprint of the Music Room, Tea Room and Ballroom match the original Great Hall and Parlour and some material exists in that building fabric, including a Tudor window frame bricked into a wall.

Both wings also follow lines of medieval walls. If you look at the wall to the right outside the gate you will see pieces of ashlar dressing and what appears to be the profile of a window mullion in the mixture of brick and int. It is probable that these are demolition rubble or waste from the chapel.

As you can see from the plan on the previous page, as you walk through the gates and cross to the steps you are walking across the original aisles and nave of the church, past the tower of the chapel now buried under the gallery and theatre next door. Once inside you are standing in the cloisters.

The bells still survive in the church of St Lawrence. Part of the crypt still exists under the Music Room with an impressive vaulted ceiling and an area of floor which appears to be the original tiles dating to somewhere around the foundation of the college.

You will find a stone plaque in the corridor to the right of the reception. Excavated in 1901 from the North aisle of the church, it is thought to be the merchant’s mark of the Browne family of Norwich. Browne rebuilt the nave of the church of St Stephen’s in 1550. This was almost certainly completed using material from the college and chapel. The Brownes are believed to be descended from the original Norman le Brun family.

A piece of worked stone found in the crypt which appears to be a mason’s mark and possibly an assembly mark. Did J. Tillit inscribe this on the hidden face of a piece pillar or vaulting or has it been repurposed as a gravestone?

IW collection

A stone plaque excavated from the north aisle of the chapel in 1901 thought to be the merchant’s mark of the Browne family of Norwich. The Brownes are thought to be descendants of the Le Brun family.

AHT collection

Cunningham 1558. The croft and site of the chapel and college can be clearly seen in the bottom left, just inside the walls between St Giles’ Gate and St Stephen’s Gate.

George Plunkett collection.

The position of the College and Chapel that existed on the site of the Assembly House in relation to the southern area of the city in the 13th century.

Nick Stone 2017 after Stephen Rowland Pierce, 1950.

Change

After the dissolution: the creation of Chapply Field House

1569–1700

After the dissolution, the destruction of chapels like St Mary de Campo gained pace across the country with an explosion in demolitions. As the Church shifted so did how it viewed and how it managed properties. This resulted in the deconsecration and sale of various buildings. In Norwich St Mary was just one loss in a long list that included St Olave, St Mary Unbrent, St Crouch and St Vedast, along with Whitefriars and Greyfriars and a huge number of other ecclesiastic buildings, churches, monasteries, priories and friaries.

Subsequently as these were dismantled, building work also started to take place. Consolidation and expansion of other churches, such as St Andrew and St Clement, and development or rebuilding of notable properties such as Augustine Steward House, Suckling Hall, and Samson and Hercules House, mortared these buildings firmly into the street pattern of the city for centuries to come.

Miles Spencer was the last Dean of St Mary, also the rector at Hevingham and Redenhall, vicar of Soham and archdeacon of Sudbury. Latterly he was the Chancellor of the Norwich diocese and is buried in Norwich Cathedral.

After Spencer’s death in 1569, what remained of the property on the site was left to his nephew William Yaxley. He in turn sold the property to Thomas Cornwallis of Suffolk, the eldest son of Sir John Cornwallis, a steward to the household of King Edward VI.

Thomas, an MP for Suffolk, was directly involved in the suppression of Kett’s rebellion of 1549 on the side of the Crown. He was captured by the rebels and only released when the Earl of Warwick’s forces quashed the revolt. Cornwallis’ support for Queen Mary saw him appointed to the Privy Council and eventually he became Comptroller of the Household before being relieved of his post when Elizabeth I, whose sympathies lay elsewhere, came to the throne.

Between 1573 and 1586 a wealthy and now retired Sir Thomas set about converting and rebuilding what then became known as Chapel of the Field House. He created a new hall and gallery, and added a kitchen, stables and tennis court. Additionally, formal gardens were laid out. The house passed to his son Charles for £1000 in 1603. Charles was an ambassador in Madrid and probably never lived here. In 1609 Chapply Field House was sold.

The property was bought by Sir Henry Hobart, Attorney General, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, and also the MP for Norwich. Such was his influence and eminence nationally that the corporation saw t to gift back parts of the site to him. They also leased the original croft and fields back to him too, creating an impressive estate. Part of the croft now forms what we know as Chapel Field Gardens.

It was a prudent move given his stature at the time. Henry is probably most famous for initiating the rebuilding of Blickling Hall more or less as we know it today, on the original site of the Falsta and the Boleyn house, using the beautiful designs of Robert Lyminge.

On Henry’s death in 1625 the lease passed to his son, Sir John Hobart the 2nd Baronet. He too was a representative of Norfolk in Parliament; and also between 1640 and 1660 a member of the much vaunted Long Parliament and another eminent character in the human landscape in both the county and the country.

Sir John married twice. He and his second wife Frances employed John Collinges, a nonconformist theologian, and had a chapel created in the house for him. After Sir John’s death Frances continued to live in and look after the house and grounds. Collinges continued to lecture in the chapel whilst being the vicar of St Stephen’s until being removed at the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Collinges was banned from using the chapel at Chapply Field House when an act was passed restraining religious meetings. He continued to lecture independently from the old granary behind Blackfriars and a building in Colegate which was eventually replaced by the Octagon chapel, one of the earliest Methodist chapels in the world.

The house passed to Sir John Hobart, the third baronet, on Frances’ death. Sir John was a staunch Parliamentarian and became High Sheri of Norfolk, a much respected man under whom Chapply Field House seemed to become the headquarters for local Whig activity in the city. The Hobarts at this point moved themselves back to Blickling Hall.

Under John and his son Henry the house was leased out with an agreement that the Hobarts could still enjoy a very limited use of two chambers when required. The site at this point falls into historical silence. Animals graze on the croft again and lodgers live quietly within the walls.

Chief Justice, Sir Henry Hobart.

Public Domain – Wikipedia/National Trust Collection.

John Collinges – Gustavus Ellinthorpe Sintzenich

A handbill advertising events at The Assembly House, January 1825. You can see this item framed next to the reception desk on the right

Assembly House Trust Collection.

A country dance in a long hall; the elegance of the couple, Analysis of beauty. Although not picturing the Assembly House, this engraving gives a pleasingly satirical flavour of the period.

1753, William Hogarth. Wellcome Images.

Detail from Cleer’s map of Norwich 1696

Moving On

Thomas Ivory and the early Assembly House

1700–1825

A series of photographs from 1949 recording the renovation work done to the Assembly House when various elements of the older buildings were uncovered. These included wall cores believed to be from Hobart’s original Chapply Field House and the remains of a wooden, 12-light Tudor window buried behind a screed coating in the north wall of the west wing.

AHT Collection.

The outside of the building features numerous graffiti that spans several centuries, this example from the front from RHC dates from 1789.

IW collection.

After the dissolution, the destruction of chapels like St Mary de Campo gained pace across the country with an explosion in demolitions. As the Church shifted so did how it viewed and how it managed properties. This resulted in the deconsecration and sale of various buildings. In Norwich St Mary was just one loss in a long list that included St Olave, St Mary Unbrent, St Crouch and St Vedast, along with Whitefriars and Greyfriars and a huge number of other ecclesiastic buildings, churches, monasteries, priories and friaries.

Subsequently as these were dismantled, building work also started to take place. Consolidation and expansion of other churches, such as St Andrew and St Clement, and development or rebuilding of notable properties such as Augustine Steward House, Suckling Hall, and Samson and Hercules House, mortared these buildings firmly into the street pattern of the city for centuries to come.

Miles Spencer was the last Dean of St Mary, also the rector at Hevingham and Redenhall, vicar of Soham and archdeacon of Sudbury. Latterly he was the Chancellor of the Norwich diocese and is buried in Norwich Cathedral.

After Spencer’s death in 1569, what remained of the property on the site was left to his nephew William Yaxley. He in turn sold the property to Thomas Cornwallis of Suffolk, the eldest son of Sir John Cornwallis, a steward to the household of King Edward VI.

Thomas, an MP for Suffolk, was directly involved in the suppression of Kett’s rebellion of 1549 on the side of the Crown. He was captured by the rebels and only released when the Earl of Warwick’s forces quashed the revolt. Cornwallis’ support for Queen Mary saw him appointed to the Privy Council and eventually he became Comptroller of the Household before being relieved of his post when Elizabeth I, whose sympathies lay elsewhere, came to the throne.

Between 1573 and 1586 a wealthy and now retired Sir Thomas set about converting and rebuilding what then became known as Chapel of the Field House. He created a new hall and gallery, and added a kitchen, stables and tennis court. Additionally, formal gardens were laid out. The house passed to his son Charles for £1000 in 1603. Charles was an ambassador in Madrid and probably never lived here. In 1609 Chapply Field House was sold.

The property was bought by Sir Henry Hobart, Attorney General, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, and also the MP for Norwich. Such was his influence and eminence nationally that the corporation saw t to gift back parts of the site to him. They also leased the original croft and fields back to him too, creating an impressive estate. Part of the croft now forms what we know as Chapel Field Gardens.

It was a prudent move given his stature at the time. Henry is probably most famous for initiating the rebuilding of Blickling Hall more or less as we know it today, on the original site of the Falsta and the Boleyn house, using the beautiful designs of Robert Lyminge.

On Henry’s death in 1625 the lease passed to his son, Sir John Hobart the 2nd Baronet. He too was a representative of Norfolk in Parliament; and also between 1640 and 1660 a member of the much vaunted Long Parliament and another eminent character in the human landscape in both the county and the country.

Sir John married twice. He and his second wife Frances employed John Collinges, a nonconformist theologian, and had a chapel created in the house for him. After Sir John’s death Frances continued to live in and look after the house and grounds. Collinges continued to lecture in the chapel whilst being the vicar of St Stephen’s until being removed at the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Collinges was banned from using the chapel at Chapply Field House when an act was passed restraining religious meetings. He continued to lecture independently from the old granary behind Blackfriars and a building in Colegate which was eventually replaced by the Octagon chapel, one of the earliest Methodist chapels in the world.

The house passed to Sir John Hobart, the third baronet, on Frances’ death. Sir John was a staunch Parliamentarian and became High Sheri of Norfolk, a much respected man under whom Chapply Field House seemed to become the headquarters for local Whig activity in the city. The Hobarts at this point moved themselves back to Blickling Hall.

Under John and his son Henry the house was leased out with an agreement that the Hobarts could still enjoy a very limited use of two chambers when required. The site at this point falls into historical silence. Animals graze on the croft again and lodgers live quietly within the walls.

Marginal drawings from Samuel King’s 1766 map of Norwich show perhaps the earliest image of the Assembly House, along with the other Thomas Ivory buildings, The New Chapel (Octagon) and the Theatre (Theatre Royal). From a facsimile of Samuel King’s 1766 map, AHT collection

From Blomefield 1806. ‘Plan of the City of Norwich’. A retrospective map. The site is marked as Chapel Field House and Cherry Yard and Chapel Field House and Garden. What is marked as site 67 is titled ‘The college of St Mary, now called Chapel-Field House’. George Plunkett collection.

The Victorians

The decline of the assembly and the new entertainment

1826-1853

Theatre Place, James Sillett, 1828.

AHT Collection.

Liszt am Flügel (Liszt on the Piano) 1840. Liszt appeared at The Assembly House in this year, his work was revived in events in 2017.

Josef Danhauser. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

By the 1830s economic circumstances in Norfolk were changing as industrialisation increased, this impacted on the local textile industries. The expansion of the railway also had an effect on the ease of travel. London became more of a focus for society families. As Sessions Week lessened in importance, Norwich lost some of its vigour and with it came a fall in income for the Assembly House.

Despite this decline, concerts, performances and dinners continued, but the guilds and political dinners were as likely to be at St Andrew’s Hall or popular inns in the city. Ticket prices for subscription dances were increased due to falling attendance to cover the costs, which gradually led to an inevitable fall in demand.

Performances received a mixed reception. A Liszt concert in 1840 received very poor reviews across the country. Niccolo Paganini the violin virtuoso also performed in the rooms.

In January 1847 Fanny Kemble, a famous actress, diarist, abolitionist and friend of Amelia Opie, received adulation for her performances of Shakespeare’s Plays. She appeared again in 1854 and 1855.

In September 1851 the opening of Norwich Waterworks was publicly celebrated. The band of the Coldstream Guards played in the Market Place and 220 guests dined at the Assembly House under the presidency of Mr. Samuel Bignold. The evening finished with reworks over the city with an estimate of 22,000 people attending. Other performances included Walter Montgomery, ‘the son of a local man who repeated from memory his recital of Othello.’

In March 1856 a Peace Ball was held to celebrate the end of the war in the Crimea with a firework display in the Market Place and Castle Meadow.

In June ‘A panorama, with the present form of variety entertainment, was exhibited for the first time at the Assembly Rooms, Norwich, by Mr. J. Batchelder.’ A national favourite, the German Reeds also appeared regularly with shows such as ‘After the Ball’ and ‘The Unfinished Opera’ and ‘Seaside studies’.

There are also various recorded examples of meetings continuing. In 1851 there was a fiery Protestant meeting under the presidency of Mr. Samuel Bignold, ‘at which were adopted addresses to the Queen and the Archbishop of Canterbury, protesting against the aggression of the Pope, and condemning the Tractarian movement in the Church of England.’ Another in 1858 was to determine ‘the advantages afforded by the Cambridge Middle Class examinations. Sir J. P. Boileau presided.’

However, things were changing behind the scenes. In December 1855 new trustees were appointed to fill gaps in the board. The property was transferred to a new Trust including Sir Robert John Harvey, Sir William Foster and Samuel Dalton. They were given the power to buy or sell the freehold should it become available.

William Schomberg Robert Kerr, the Marquess of Lothian, owned many properties including Blickling Hall. He also owned the freehold for the Assembly House. In June 1856 he sold this to the Trustees for £200.

In September the Estate was put up for sale at a public auction in the Royal Hotel in Norwich Market Place. It did not sell. As a result, in 1857 the estate was broken up into more manageable lots. The West wing and the gardens were sold to Frank Noverre. He in turn sold part of the garden a year later. The Assembly House and east wing were sold to Benjamin Bond Cabbell. Documents dated June 22nd 1861 are the first which use the name ‘Assembly House’.

Cabbell was 80 when he bought it, an energetic man; Oxford educated, called to the Bar, deputy Lieutenant for Middlesex and Norfolk, and an MP for St Albans and Boston. He was also a fellow of the Royal Society and an acknowledged philanthropist and Freemason.

Consequently all the Norwich lodges, except the Union, met for free. For the next 15 years the Assembly House was referred to as the Masonic hall or the Freemasons’ Hall. Cabell lived in Cromer Hall. His local philanthropy extended to financing the building of Cromer lifeboat station and the building of a new lifeboat which was named after him.

In the autumn of 1872 the Assembly House was closed for repairs; these were apparently quite extensive and were probably due to lack of general upkeep over the previous decades; no real changes were made to the fabric.

Benjamin Bond Cabbell died in 1874 at the age of 92. He left the building to his cousin, John Bond Cabbell, who in 1876 sold it to the Girls’ Public Day Schools Trust. Another new phase in the building’s history had begun.

The Noverres

Ballet, swords, and the spirit of dance

1754-1900

Jean Georges Noverre

Engraving from The Chevalier Noverre - C.E. Noverre.

Francis Noverre 1773 - 1840.

Aviva archive.

Frank Noverre 1806 - 1878.

AHT collection.

There are adverts advertising his services as a dancing master in the 1790s in the city and he also seems to have had a circuit of teaching across the region. Augustin died in Norwich in 1805.

From 1813 to 1825 Francis had a room for his academy in the vicinity of Clement Court and Redwell Street. By 1825 he was advertising his academy in Theatre Square, although it seems he still used his smaller rooms too.

Francis married Harriet Brinton, the daughter of the manager of the Theatre Royal who lived in Theatre Square. While it is not clear exactly where the academy was, there is a room upstairs with an elegant coved ceiling, which may have been the dancing room.

From about 1835 the Noverres were living in the West wing. Academies may well have been held here too, possibly in the Sexton Room which was referred to as ‘Miss Wisp’s Drawing Room’. The academy run by the Noverre family certainly flourished here for the next 75 years. Francis was also a founder member and director of the Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society. He retired in February 1837 and died in 1840.

Francis’ son Frank took over stewardship of the school and also continued the family’s involvement in Norwich Union. Dancing lessons were held every Tuesday morning for ladies only and Tuesday and Thursday afternoons for ladies and gentlemen.

The family were also involved, with Frank’s daughters advertised in the Norwich Directory as ‘professors of the harp and singing, and of the concertina and singing’. The lessons were given in the house; it is believed the annual ball and a special juvenile ball held for the children they taught took place in the Assembly House.

In September 1857 Frank bought the West wing and garden and was finally able to fulfil a dream. He built the Noverre Rooms which opened in 1858. He left his mark not just in the name now synonymous with the city, but also in the fabric of the building; his family’s initials are carved into the brickwork by the side door of the Ballroom: Ellen Elizabeth, Ada Emily, Francis Josephine, Virginia, Mary Louise, Sophia Harriet and Sarah Anne, then his sons, Charles Edwin, Frank William Bianchi and Richard Percival.

Frank died in 1878 aged 71 having built up an extensive practice. He was involved in various societies in Norwich including Norwich Choral Society and he was a founder and honourable secretary of the Norwich Philharmonic. The property was left to his wife Sophia; she in turn left it to two of her sons, Frank William Bianchi and Richard Percival. Richard sold his half to Frank.

Frank was better known as a violinist and for his involvement in orchestras. Part of an ever musical family, his brother Charles Edwin was well known as a music critic and was also organist and choirmaster at St Stephen’s church for 21 years before going to the London office of the Norwich Union.

The property was sold to the Girls’ Public Day School Trust in 1901 to augment the main house which the school was already using. It is perhaps rather fitting then that Josephine Diver, Frank’s granddaughter, was a senior math’s mistress at the Girls’ High School whilst it was in the Assembly House. She also produced plays for the school for many years. She retired in 1933 having helped mastermind the move of the school to Eaton Grove. She also left portraits of the Noverre family to the Assembly House Trust.

It is toting that in St Stephen’s church on a wall of the chapel that served both the Hobart and Noverre family is a memorial tablet to this remarkable family, which so greatly influenced the musical life of their chosen home city.

David Garrick of London’s Drury Lane was always searching for something new in an ongoing competition for audiences in Covent Garden. He found the perfect act in 1754 at the Opera Comique in Paris in the form of Swiss Jean Georges Noverre’s ballet Les Fetes Chinoises, Jean Georges had trained under Dupie, a French dance master. He had performed extensively for Royalty in France and was created a Chevalier of the Order of Christ.

Garrick entered into negotiations and transferred The Chinese Festival to London for six weeks. In the company were to be Noverre’s wife, his two sisters, his sister-in-law and his younger brother, Augustin.

With the smell of war in the air there was gathering anti-French feeling. The family, who many in the audiences assumed to be French became a target. A performance in front of the King ended with noise and violence which the King and his party apparently enjoyed hugely.

The ballet run was paused for a time then put on again, but the opposition grew more violent with each show. On the night of November 16th it got completely out of hand and a near riot ensued. Sets and furniture were smashed. Swords were drawn and in the fighting Augustin Noverre ran someone through. He was forced into hiding. The man who was injured subsequently made a full recovery.

The story is somewhat unclear from here. It is believed Augustin may have hidden in the Huguenot community in Norwich. It is also possible that he fled here, then divided his time between Norwich and London before finally settling.

His son Francis was born in the parish of St Clement Dane in London in 1773. It is recorded that Augustin and his family lived in Chantry Court, next door to the Assembly House, a location which was lost to road widening in the 1960s.

Chantry Court pictured in 1936, now demolished, it stood next to the Assembly House. This is believed to be where Noverre family lived.

G. Plunkett collection, 1936.

Facsimile of an advertisement for Mr Noverre & Son’s dancing lessons at the Assembly House (Theatre Square), 1835.

Aviva Archive

Decline

A school, a warehouse and a war.

1901-1943

The Girls’ High School, Banquet room, 1922.

AHT Collection.

The Girls’ High School, Banquet room, 1922.

AHT Collection.

The Assembly House front view in the 1940s before reconstruction.

AHT collection.

Caleys After the April 1942 attacks

IW collection, believed to be George Swain.

The beginning of the 20th century saw the site well established as the Norwich High School for Girls, with minimal changes made to the buildings. A few extra partition walls were established to divide large rooms into classrooms. The West wing was still owned and lived in by Frank Noverre; this was bought by the school along with the relatively newly built Noverre Ballroom in 1901.

Theatre Square at the front of the building was open to the road and used as a playground. Theatre Street was a busy thoroughfare with a newly built tram line. Concerns were expressed about safety, a concession was made and the playground area was contained by the railings and gates we see today, with another area allocated to the highway. The original lamps which surmounted the gate posts are now axed to the front of the building.

In 1933 the building again became vacant as the High School moved to more spacious grounds at the former house of John Harrison Yallop, Mayor of Norwich, in Eaton Grove.

The building was again up for sale; it transpired that the School Trust had made an application to develop the site. A local company had also registered an interest in buying it, but only if it could be developed. The buildings did not sell due in part to it being registered as an ancient monument. It was felt that further action was needed to ensure the property was protected. A meeting between the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Trust and the Norwich Society in 1935 resulted in a resolution being passed to preserve the Assembly House for the city. ‘The buildings area a very fine examples of the style of the middle of the eighteenth century and of local (if not national) importance being the work of the architect Thomas Ivory and being connected since its erection in 1754 with the history of the city: also this site and the fourteenth century crypt beneath it preserves the memory of the meeting place of one of the earliest Civic Assemblies in the kingdom.’

Graffiti on the outside of the building dating to its use as part of the YWCA in the 1930s

IW collection.

The buildings were saved from destruction, but that was all, standing more or less empty. Parts were rented out to pay the mortgage. The Ivory Rooms became a warehouse for bicycles and other parts of the building were used as stores for Caley’s chocolate factory. By 1938 the western wing was also being used by the YMCA and YWCA as a hostel.

Oliver Messel by Yvonne Gregory

(Wikipedia)

In 1938 a consortium including Henry Jesse Sexton, Sir George White and Alan Rees Colman bought the building initially with plans for expanding its use with the YMCA and YWCA. Boardman and Son were asked to prepare plans. A variety of options were looked at, including building a lecture hall and theatre on the car park and proposals to use the Noverre Ballroom and the Music Room as women’s and men’s gymnasiums. These were all promptly shelved as the Second World War loomed. The building remained partially empty and decaying.

It was by chance and good fortune that while working for the War Office, Oliver Messel, previously an eminent stage and lm set designer, was posted to Norwich. He had a studio at 70 Bishopsgate and a workshop in the shed behind the former workshop of J Short near the cathedral which had already been requisitioned. Messel took to exploring the city, and at some point in 1940 chanced upon the Assembly House in a then semi-derelict state. He was rather taken with what he found and appalled by the state of such a fine Georgian building.

It would appear that in December, on his advice, the buildings were requisitioned, becoming the Eastern Command Camouflage Office and Camouflage factory. Roland Penrose, the surrealist, lectured to the officers and men at the Assembly House. And it was at Messel’s insistence that Christopher Hussey visited and wrote about the building for Country Life. Messel also alerted his brother in law at the Georgian Society of the building’s historical importance.

The building came under the command of Lieutenant Vivian De Sola Pinto: a poet, literary critic and historian who fought alongside Siegfried Sassoon during the Great War. The rooms were cleared of bikes and furniture. Paint, canvas and hessian and plaster replaced dust and school fittings. Camouflage patterns and models were laid out on the huge floor spaces and hung from the walls where festoons, drapes and portraits had hung over a century before.

In April 1942 the Baedeker raids began. The first Luftwaffe raid on the 27th focused on transport, industry and residential properties. The second on the 29th concentrated more on the commercial centre, around the Assembly House. Dorniers and Junkers swept in, dumping high explosives and then dropping incendiaries into the gaps they created. Serious res raged through the night. Nearby Buntings, Woolworths and Curls were burnt out. Caley’s chocolate factory behind the Assembly House was reduced to heat-distorted walls and smoking rubble, the smell of burnt sugar drifted across the city.

Fires raged around the Assembly House. Messel fortunately had noted the lack of any re watch on the building and had instated one: the men dealt with multiple incendiaries during the second raid which hit the building; there was some damage, mostly to the roof of the East wing, plus blast and vibration damage.

In 1944 as the South and East of England filled with D-Day troops, Messel organised an event. The building was dressed appropriately, props were created using the men’s camouflage skills, theatre design and lighting techniques. Local dignitaries and the military were invited. By highlighting the building, Messel paved the way and Henry Sexton saw an opportunity to drive it forward.

The Assembly House 1940s. AHTPHP collection.

The Assembly House 1940s. AHTPHP collection.

The Assembly House front view in the 1940s before reconstruction. AHT collection.

Regeneration

Building the future – modern development and the trust

1944-1994

The post-war period found the building in a poor state, with no real upkeep having been completed since the 1930s. Of the original consortium Henry Sexton and Sir George Ernest White remained, but sadly Alan Rees Colman died in a flying accident while on active service.

Portrait of Henry Jesse Sexton, seated in grey suit signed and dated 1951, by Henry Lamb

AH Collection, on display above lift.

Despite the circumstances and the condition of the building Henry Sexton wasn’t put off, and whilst in discussion with another enthusiastic supporter Arnold Kent, they started to imagine a different future for the buildings; one where the Assembly House became a centre of the arts. A committee was formed chaired by J.B. Hales, with Arnold Kent, Nugent Monck, Reginald Pareezer and Andrew Stephenson representing interested parties from theatre, arts, lm, and education.

A preliminary report was presented in June 1943. The initial aims were to acquire and restore the Assembly House, add a theatre and cinema, with the premises given to trustees for the use of the City of Norwich’s centre for the arts.

Part of the original plan was to transfer the Norwich Players from the Maddermarket Theatre, with the Maddermarket Theatre Trust running the Assembly House with the assistance of the council. The Theatre was planned for the Noverre Ballroom. The centre would also be made available for concerts, recitals and art exhibitions. One proposal was for a gallery for the collection of Norwich School paintings held by the Colman family.

There were negotiations due to the differing views on how the Trust should be comprised and whether it should be presented to and run by the city or if it would fare better as an independent trust. Eventually Sir Ernest sold his share to Henry Sexton and in March 1945 the H.J. Sexton Norwich Arts Trust was formed. The members were Henry and Eric Sexton, Herbert Gowen, Charles Hammond, Percy Jewson MP, Frederick Jex, Arnold Kent, Walter Nugent Monck, and Edward Williamson, the then Lord Mayor of Norwich. Architects Charles Holloway James and Sir Stephen Rowland Pierce, who had designed City Hall, were appointed. Pierce eventually completed the plans on his own.

The state of the building was also a problem, with Pierce commenting he had to ‘battle with decay, dry rot beetles, neglect and blitz’. Rot appeared everywhere, foundations had been sliced into for previous alterations, there were areas that required underpinning, ceilings falling in and damp.

On the plus side, the two-storey section added to the Noverre Ballroom to house classrooms made a perfect projection room at the exact height required for raked seating. The theatre had to be abandoned due to conversion costs, a disappointment given the original vision of it extending the work of the Maddermarket.

Working on the footings, 1949.

Some areas of the original Ivory house had vanished forever; the stairs had been removed a century before. Cabball and later the High School had made only a few changes; some partitioning in the Music Room had to be removed. The organ gallery was altered; the school laboratories were repurposed. The Steward’s house was demolished to make way for cloakrooms.

The East wing, which retains elements of its Elizabethan structure, was repaired and renovated, part of which forms the manager’s house. The drive was resurfaced and the thicket of shrubs removed, ironwork was cleaned with the details picked out in gilt.

Finally the rooms were named, commemorating people connected with the building’s history: Hobart, Ivory, Bacon, Pierce, Kent, Messel and Sexton, and the Noverre Cinema replaced the Ballroom. On the 23rd of November 1950, the Assembly House was Finally presented to the people of Norwich as a centre for the arts.

The final piece was put in place in 1954. The pool in the forecourt was instated, completed with James Woodford’s sculpture of a boy. His work, visible on the main doors at City Hall, unwittingly perhaps re-establishing the relationship between the city’s crafts, guilds, trades, and citizens and the building.

For the next 45 years, the Assembly House played host to events, films and performances, dinners, exhibitions, and meetings. The Assembly House had again cemented its place in the city as a place to ‘Assemble’. Then on April 12th 1995 something terrible happened.

The Music Room with the gallery removed and the platform under construction, 1948/1949.

The Noverre Cinema

Projectionists at the Noverre Cinema, 1973.

The Noverre Cinema with raked seating installed and windows blanked out, looking towards the projection room at the rear.

Designs for James Woodford’s sculpture in the forecourt fountain.

After the fire

The new improved Assembly House

1995-2021

The post-war period found the building in a poor state, with no real upkeep having been completed since the 1930s. Of the original consortium Henry Sexton and Sir George Ernest White remained, but sadly Alan Rees Colman died in a flying accident while on active service.

On August 12th 1995 a huge re ripped through the roof of the Grade 1 listed house. It destroyed the structure which largely collapsed, damaging original carvings and plasterwork, and left a pall of smoke across the city.

No time was lost under general manager Ben Russell-Fish and Eric Sexton. The next day, the trustees agreed to the restoration of the building and started fundraising immediately. And with some assistance from the National Lottery Fund invested £400,000 in new facilities, including provision for the disabled, new kitchens and better re detection. Exhibition areas and lighting were upgraded and climate control installed for exhibitions.

The plans were developed with Purcell Architects. The restoration work used experts who had been involved in the restoration of Windsor Castle and included colour schemes created by Nicholas Herbert. The fire, smoke and water-damaged plasterwork was painstakingly replaced with detailed handmade reproduction Georgian facsimiles.

22 months later, two months ahead of schedule, the improved Assembly House reopened on the 14th February 1997.

Today, the Assembly House continues as before, a venue used by a mix of clubs and societies for their regular meetings, including the Norwich Society, the Norwich Music Society, the Norwich Opera Club, the Archaeological Society, the Historic Arts Trust and the Writers’ Circle. The Open University uses it for its examinations and many art and craft exhibitions are staged in the building. It has a fabulous restaurant, and hosts a hugely diverse range of events, as likely to hold a blood donor session as it is to play host to a lm crew or a lm show or a wedding.

Craftsmen using skill and dedication repairing the plasterwork in situ.

AHT collection.

Craftsmen working on repairs to the Assembly House roof.

IW collection.

Making replacement plaster detailing and repairing sections of existing work.

AHT collection.

Surviving original oak timbers, so sound and re-hardened they were retained in the roof structure.

IW collection.